|

in the border between folk and artistic expression

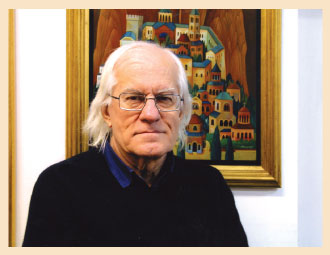

Katia Kilessopoulou

Dr. Art Historian

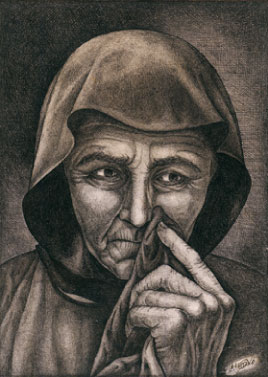

Inspired by the folk art and his childhood experiences, Thanassis Bakogiorgos has become the perpetuator of the Greek illustrative tradition.

Although he came in contact with the modern artistic trends, having lived abroad for a period and hosting in his gallery "Panselinos" various trends of contemporary Greek art, it was the visions from the legends and the fadeless impression of his birth land during his childhood and adolescence that were revived in the mature period of his painting.

The hard conditions of living –orphanhood, poverty, war devastation– were balanced by the contact with the magical nature of Evritania, Mt. Agrafa, grandmothers' tales about fairylands, the pixies of the rivers and bridges, the stories about the feats of the heroes of the 1821 Independence War, the beauty of the stone-built houses with the embellished exterior decoration. The emotional charge which came from the fund of memory, acts, works, found an early passage to expression through painting and plastic art. The clay of the village was used as a raw material to mould, at the age of 7-10, the figures of Karaiskakis, Botsaris, Katsantonis, Athanassios Diakos, heroes of the liberation struggle, who were connected to the land.

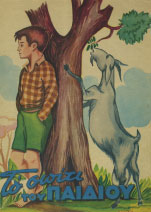

The early artistic expression, barely accepted by the environment in times when the conditions of living imposed other priorities, gave him however the first chance and encouragement to keep on, when the magazine "House of the Child" started publishing his adolescent sketches. Thus, the course to applied arts was plotted.

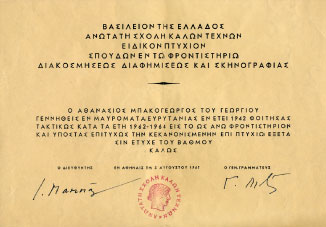

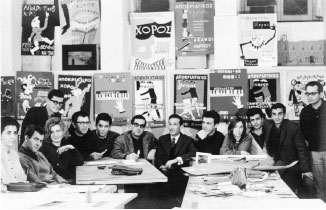

During the '60s, interior decoration, sketching, caricatures and magazines' illustrations provided him the necessary financial support. His studying at the Stage Design Department of the Higher School of Fine Arts enhanced his knowledge of the techniques and structural models, necessary supplies for an artist who feels like a master.

Although he started early to draw with china ink, the dedication to painting, at first with watercolours is dated from the end of the '70s. The human figure, mostly female, and the pairs are dominant during the first period of his work (1978-1988). Abstractive, minimal in colour, formulated with wide brushwork, focused mostly on a face and particularly on the contemplative, melancholic gaze; in cases of pairs, it sometimes takes on an idolized tint of tender engagement emphasizing on the vivid elements, and sometimes it merges the two figures effacing the physiognomic details. Some individual female forms gradually obtained something from the unearthly, emotive look of the 'Fayyum' portraits.

It is remarkable that the anthropocentric subjects are abandoned by the end of the '80s, just like tempera. The artist is now working with acrylics in thematic unities from which the human form is completely absent. These unities, often worked on in parallel, can be categorized in: landscapes –mountainous, coastal– chapels, Byzantine cities, medieval towns, monasteries, the Meteora and the Holy Mountain (Aghion Oros).

|

| First Sculptures. Mavrommata, Evritania, 1955 |

In the landscapes, most of the time inspired by the Dorian simplicity of the Evritanian geomorphology, preserve for a while the abstraction observed originally in the human forms. A low colour scale which covers flat surfaces with elusive strokes renders the mountainous bulks and the waste lands. The smooth sea –at times only slightly wrinkled– and the barely processed, in terms of colour, sky, act as frames – backgrounds on which the scenery is projected. The addition of flora leads to a more and more picturesque landscape where the chapels find their place in different variations of architectural types. The absence of plasticity in the almost flat formed synthesis is balanced by the detailed descriptions of the trees and the sparse vegetation.

The artist's connection to the Byzantine past of Thessaloniki and Aghion Oros stirred historical, homely memories but also roused the juvenile viewpoint. His now exclusive interest in painting is the revival of a glorious, powerful cultural past, transformed through imagination. As the folk artist does not feel the need to faithfully resume a prefabricated standard but keeps the narrative character, adjusting the motifs and illuminative types, in the same way Bakogiorgos uses as a base old maps, texts, visual stimuli from monuments derelict or untouched by time, churches, bridges, castles, monasteries, murals, in order to 'reconstruct' as a perfectionist and therefore arbitrarily, images of the past, to tell his own fairytale with the illusive precision of an eye-witness. The whole approach is illusive not only due to the stage design of space but mostly, due to its unreal order, the persistent symmetry, the lack of everyday elements, basically effacing every 'disturbing' trace of ordinary, meddling human activities.

His panoramic Byzantine cities, the embattled monasteries, the medieval towns and harbours, scattered in hills and lacy coasts, gain an ageless character through the scarlet, the golden ochre, the glare, the still atmosphere, the use of multiple perspective, the identical detailed snapshots, like images 'frozen' in time.

Besides Monemvassia and Mitylene, most of the views are dedicated to Thessaloniki. He approaches the city from above and front. From the panoramic, cartographical views, reviving the subject of the cityscapes, he passes, like focusing with a magnifying glass, to apportioned depictions of the inshore areas of the harbours, the White Tower, the monuments downtown, to the city edges that adjoin nature. Cupolas, tall church towers, gabled roofs with gablet corners, arched gates, oblong multi-lobes, windows, peristyles, chambered archways, clumps of pines and fir trees, diversify the illustration. The desolate streets, the lack of colour values and the static synthesis form a 'mnemonic image for ever', a hymn to the glorious past of Thessaloniki, like the one kept in the collective unconscious, beyond historical annotations and human controversies. His regard to Constantinople is at the same wave.

|

|

|

|

| Covers for the magazine «To spiti tou Paediou», 1959-1962 | |

The works with Meteora as a subject are noticeably different than those of the Aghion Oros monasteries. The former are approached in a clearly glorifying way with a surreal style. The transcendental character of the Meteora is tightened not only by the sublimity of the vertical rocks –looking like pillar saints– or by the fabulous cloistral architecture but also by the anti-realistic colour, red, golden, blue. Whereas in the monasteries of Aghion Oros a detached realism dominates, as if the need of personal interpretation respectfully withdraws, which under the narrow subjective perception would stress or omit something from a record of a thousand years of cultural heritage.

The manual character of the traditional art bore an unabated charm on Bakogiorgos. Identified with the mentality of the folk craftsman, who is content to be expressing himself through painting walls, ceilings, chests, like a contemporary artisan engaged for years now, in the creation of the same decorations, familiar from the 18th century, in private and cloistral areas.

Geometrical patterns, baroque and rococo floral syntheses, fresh girls with pigeons or baskets of plenitude in hand, enamoured sceneries, vocalists, fortunate ships, miniatures of ports and cities, are the themes that decorate wooden navel-shaped roofs, elaborate mirrors, trunks, mezzanines, skylights.

Bakogiorgos' works have a special impact on the broad public. This fact is explicable, since, during dark times such as ours, when ways and manifestations of life are threatened by the extinction of the Greek spirit, the return to an idealised, prosperous past, offers a reliable haven. With his art of solace, he takes us beyond the insecurity of the present.